This morning’s e-mails contained a spam message titled “End the annoying obesity now.” I had to laugh, as I have just discovered my own secret to rapid weight loss, namely methylprednisolone. Maybe I should run out and patent the “CLL Miracle Diet” before some doctor -- like Tom Kipps or Januario Castro -- gets inspired by the example of Dr. Robert Atkins and decides to it.

One side effect of taking steroids can be weight loss, especially if you are a bulky CLL patient like me. My experience, dropping 20 pounds in nine days -- about 10% of my body weight -- is consistent with what has happened to some other patients I know about.

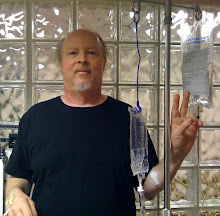

As you will recall, I began taking 72 mg of methylprednisolone (MP) daily starting March 14 for a sudden case of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). High doses of steroids (1 mg/kg prednisone up to 2X daily) are the standard frontline treatment for AIHA -- and in my case they are working. (For those of you keeping score: My hemoglobin was up to 11.3 as of yesterday, as opposed to its nadir of 8.9 on March 14, and I am almost starting to feel normal, or as normal as I get. Hematocrit went from a low of 26.9 on March 12 to 34.8 yesterday. Haptoglobin levels, which had been as low as 10, were up into the 70s after only two days on the steroids, 34–200 being the standard range.) I expect my red counts to be normalized very soon, and one of these days I will report on my theory as to why I developed AIHA in the first place.

The AIHA reared its ugly head -- I am reminded of the old Monty Python sketch "Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition” -- just as I was undertaking low-dose Rituxan three times a week for 12 weeks as part of a plan to deal with CLL. My hem/onc and I had planned to add some low-dose MP toward the middle of that process to squeeze CLL out of the nodes and  spleen, after first getting the peripheral blood counts down. This was the plan anyway, and it was completely upended by the AIHA diagnosis. In the immortal words of my doctor, who came rushing into the infusion room with scripts in hand, “How would you like to start the steroid part early?”

spleen, after first getting the peripheral blood counts down. This was the plan anyway, and it was completely upended by the AIHA diagnosis. In the immortal words of my doctor, who came rushing into the infusion room with scripts in hand, “How would you like to start the steroid part early?”

This turn of events has interesting consequences for the CLL as well as the AIHA. Readers of this blog know that I have long been interested in the concept of Rituxan + HDMP (high dose methylprednisolone), the protocol that has been used successfully in chemo-naïve patients at UC San Diego (and thus the source of my reference to Drs. Kipps and Castro in the first paragraph). CLLers following this protocol also know there is debate in the medical and patient community about its advisability, with some people swearing by it and others swearing you have to be crazy to do it. My own experience with MP at much lower doses, as well as with Rituxan in combination, is giving me some interesting insights into the issue. I promise to go into them in detail.

In the interim, suffice it to say that my AIHA treatment plan has had big consequences for my CLL, which brings us back to the weight loss. As you debulk, the weight has to go somewhere. Fortunately, methylprednisolone has lympholytic activity -- that is, it kills off CLL cells -- which are passed as urine. But it is by no means a miracle worker in this department. There are three compartments where CLL hides: the lymphatic system (including spleen), the bone marrow, and the peripheral blood. Steroids push the CLL out of the first two; what isn’t killed circulates in the peripheral blood, driving the absolute lymphocyte count upwards. If you let the CLL just float there, once you have stopped the steroids it is only a matter of time -- a couple of weeks, a month -- before the white trash is back in the other compartments, making babies and cleaning up after the hurricane.

This is why my hem/onc and I will meet Monday to go over the situation; my MP dosage was cut by 50% two days ago and I will probably be off of it entirely soon. Perhaps we will consider upping the Rituxan dosages to take advantage of this window of opportunity.

Not all of the weight loss is CLL. Muscle wasting is one side effect of steroids and it appears to be part of the problem in my case. (Muscles can be built back up, so it isn’t permanent.) This is why I ended up at a General Nutrition Center store yesterday, buying one of those clown-sized jars of “the world’s most powerful weight gain formula.” High protein, low glucose, a thousand calories in every 16 delectable ounces.

Indeed, the challenge for the past week has been to eat enough calories. Like almost everyone reading this, most of my life has been spent with the opposite problem. Suddenly I find myself in a bizarro world where ingesting exessive calories is a good thing. The other day, for the first time in my life, I ate steak and eggs for breakfast, swimmin g in butter. It is a sad day when you troll the nutritional information sheet for Burger King looking for the highest-calorie sandwich you can find (Triple Whopper with Cheese, 1230 calories). For once I am free -- nay required -- to eat with abandon, but I have to avoid things with lots of sugar, as steroids can raise glucose levels. I have a glucose meter at home and while my levels have gotten a little high at times, they have stayed well away from the magic number of 200, which is when we radio Houston and tell them we have a problem.

g in butter. It is a sad day when you troll the nutritional information sheet for Burger King looking for the highest-calorie sandwich you can find (Triple Whopper with Cheese, 1230 calories). For once I am free -- nay required -- to eat with abandon, but I have to avoid things with lots of sugar, as steroids can raise glucose levels. I have a glucose meter at home and while my levels have gotten a little high at times, they have stayed well away from the magic number of 200, which is when we radio Houston and tell them we have a problem.

So I am eating more and enjoying it less. On the plus side, I haven’t looked this trim in about 20 years. There is an opportunity here, post-steroid, to build back muscle and stay at a lower, healthier weight. And, of course, there is an opportunity here to deal with the CLL in a more meaningful way than I have in the past, since I debulked much better than I would have imagined.In the meantime, I have a spring in my step -- both from my returning red counts and my lighter weight. Thanks to all of you who have written me with your messages of support, as well as with some invaluable advice about managing life with steroids. The one thing I keep saying about chronic lymphocytic leukemia is that we are all in this journey together, and that our caring for one another makes an incalculable difference. I have learned first-hand recently that this is true.Now I think I'll go have lunch. Bucket of chicken, anyone?